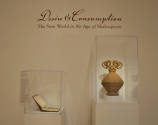

Desire and Consumption: the New World in the Age of Shakespeare

Saturday, January 14, 2017 - Sunday, April 09, 2017

“Have we devils here? Do you put tricks upon’s with savages and men of Ind?”

—Stephano, regarding Caliban in The Tempest

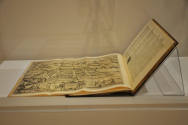

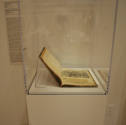

Although Shakespeare set The Tempest (1610) on a small island off the coast of Italy, scholars now argue that he drew inspiration for the setting, several narrative themes, and the figure of Caliban from the newly encountered Americas. The quote above illustrates Stephano’s ignorance about Caliban, the island’s only native inhabitant in Shakespeare’s romance The Tempest, and is representative of common early modern rhetoric surrounding encounters with people in the New World. Presented as a part of Shakespeare at Emory, this exhibition explores the various effects of colonialism and consumption in both the constructions and realities of encounters between the Amerindian “savages” and European contemporaries of Shakespeare. It features volumes from the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library spanning the late 16th–17th centuries, and illustrates not only the disastrous and destructive conflicts between European and Amerindian cultures, but also the harsh realities and narratives of European travel to the New World. These volumes are brought together around William Shakespeare’s final solo-authored play, The Tempest, displayed here in the Fourth Folio of his collected works (1685), and include a manifest of individuals destined for the Jamestown colony and eight volumes of the monumental Americae series (1590–1625) by the Flemish engraver Theodor de Bry (1528–1598) and his sons.

Commercial desires, curiosity, and a conversion mentality drove many artists to accompany voyages across the Atlantic. The first serious attempt to collect travel accounts and images that convey aspects of life and culture on the American continent, the Americae volumes cover exploits by nations involved in the Atlantic colonial enterprise particularly Spain, England, and France. The exhibition traces the ways in which these engraved illustrations of Amerindian culture and bodies influenced the construction of literary characters such as Caliban, who is identified in the play text as “a savage deformed slave,” and also affected European interpretations, subjugation, and consumption of real people, their behaviors, and cultures.

Alongside these volumes, this exhibition highlights the Carlos Museum’s vast collection of Art of the Americas. These works of art, from Central and South America, represent cultures with similar lifeways, art-making processes, or ceremonial practices to those represented in de Bry’s Americae volumes. Such objects were often brought from the New World to Europe, devoid of original signification and purpose, and thus began to shape European economies, traditions, and the thirst for knowledge and empire. These objects, placed in conversation with the works on paper, question the hegemonic narratives of Shakespeare and de Bry, whose Americae series became a prevailing source of information about the so-called New World. Viewing these seemingly disparate items alongside one another encourages conversation about the narratives of conquest and colonization, at times grounded in religious distinctions, fear of the unknown, or in national pride, and about the influence of consumption on both the conqueror and the conquered.

—Stephano, regarding Caliban in The Tempest

Although Shakespeare set The Tempest (1610) on a small island off the coast of Italy, scholars now argue that he drew inspiration for the setting, several narrative themes, and the figure of Caliban from the newly encountered Americas. The quote above illustrates Stephano’s ignorance about Caliban, the island’s only native inhabitant in Shakespeare’s romance The Tempest, and is representative of common early modern rhetoric surrounding encounters with people in the New World. Presented as a part of Shakespeare at Emory, this exhibition explores the various effects of colonialism and consumption in both the constructions and realities of encounters between the Amerindian “savages” and European contemporaries of Shakespeare. It features volumes from the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library spanning the late 16th–17th centuries, and illustrates not only the disastrous and destructive conflicts between European and Amerindian cultures, but also the harsh realities and narratives of European travel to the New World. These volumes are brought together around William Shakespeare’s final solo-authored play, The Tempest, displayed here in the Fourth Folio of his collected works (1685), and include a manifest of individuals destined for the Jamestown colony and eight volumes of the monumental Americae series (1590–1625) by the Flemish engraver Theodor de Bry (1528–1598) and his sons.

Commercial desires, curiosity, and a conversion mentality drove many artists to accompany voyages across the Atlantic. The first serious attempt to collect travel accounts and images that convey aspects of life and culture on the American continent, the Americae volumes cover exploits by nations involved in the Atlantic colonial enterprise particularly Spain, England, and France. The exhibition traces the ways in which these engraved illustrations of Amerindian culture and bodies influenced the construction of literary characters such as Caliban, who is identified in the play text as “a savage deformed slave,” and also affected European interpretations, subjugation, and consumption of real people, their behaviors, and cultures.

Alongside these volumes, this exhibition highlights the Carlos Museum’s vast collection of Art of the Americas. These works of art, from Central and South America, represent cultures with similar lifeways, art-making processes, or ceremonial practices to those represented in de Bry’s Americae volumes. Such objects were often brought from the New World to Europe, devoid of original signification and purpose, and thus began to shape European economies, traditions, and the thirst for knowledge and empire. These objects, placed in conversation with the works on paper, question the hegemonic narratives of Shakespeare and de Bry, whose Americae series became a prevailing source of information about the so-called New World. Viewing these seemingly disparate items alongside one another encourages conversation about the narratives of conquest and colonization, at times grounded in religious distinctions, fear of the unknown, or in national pride, and about the influence of consumption on both the conqueror and the conquered.