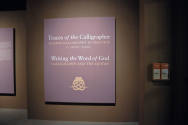

Traces of the Calligrapher: Islamic Calligraphy in Practice, c. 1600-1900 and Writing the Word of God: Calligraphy and the Qur'an

Saturday, August 28, 2010 - Sunday, December 5, 2010

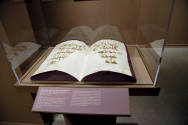

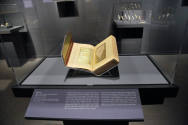

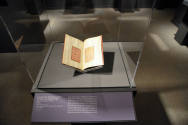

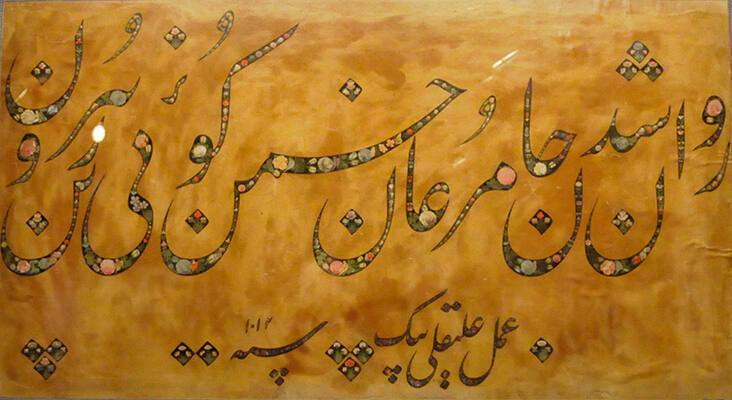

Together, Traces of the Calligrapher: Islamic Calligraphy in Practice c. 1600-1900 and Writing the Word of God: Calligraphy and the Qur'an examine some of the major developments that took place in the art and practice of calligraphy, Islam's most esteemed art form, from the 7th to the 15th century, and the artistry of the tools used to write the sacred text.

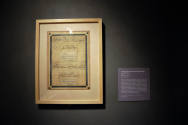

Muslims believe that the Qur'an is the written record of a series of divinely inspired revelations, the actual word of God, mediated through the angel Gabriel to the Prophet Muhammad in the 7th century. The fact that the revelations had come to Muhammad in Arabic, along with the high status accorded to writing in the Qur'an, created a new prestige for the Arabic language, its written form, and its visual expression. Although no other book matched the Qur'an in holiness—as God's eternal word—the Qur'an elevated the status of all books, and the art of writing.

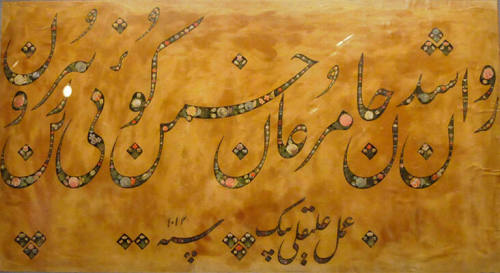

In the Islamic world, the practice of calligraphy constitutes an expression of piety. Historically the writing of Arabic script was considered an exemplary activity for men and women of all stations due to its association with the Qur'an. In a literal sense, calligraphy leaves a trace of the physical movement of the hand. In a more abstract sense, it is also a material record of thoughts transformed into speech and then into writing. In the Islamic lands, calligraphy is understood to leave a trace of the writer's moral fiber, and the quality of writing is believed to reveal the writer's character and piety. The tools to create masterful script convey the elegance of this esteemed art form and reveal the skills of diverse artisans, from paper makers and bookbinders to gold beaters, illuminators, and metalworkers.

The varied works of calligraphy on display—from practice alphabets to elaborately finished manuscripts—serve as traces of individuals, belief systems, and cultures. The costly and exotic materials lavished on writing instruments also document the international trade of the period from 1600–1900 and create a rich material legacy that fuses aesthetics and piety.

The exhibitions were organized by the Museum of Fine Arts Houston and the Harvard University Art Museums, and were curated by Mary McWilliams, Norma Jean Calderwood Curator of Islamic and Later Indian Art at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, and David J. Roxburgh, Prince Alwaleed bin Talal Professor of Islamic Art History at Harvard University.

Support for the exhibitions in Atlanta has been provided by Emory University, the Ansary Foundation and the Honorable Mrs. Hushang Ansary, Mr. and Mrs. Vahid Kooros, His Highness Prince Aga Khan Shia Ismaili Council for the Southeastern United States, Malani Jewelers, Imperial Fez, and Emory's Department of Middle Eastern and South Asian Studies.

Muslims believe that the Qur'an is the written record of a series of divinely inspired revelations, the actual word of God, mediated through the angel Gabriel to the Prophet Muhammad in the 7th century. The fact that the revelations had come to Muhammad in Arabic, along with the high status accorded to writing in the Qur'an, created a new prestige for the Arabic language, its written form, and its visual expression. Although no other book matched the Qur'an in holiness—as God's eternal word—the Qur'an elevated the status of all books, and the art of writing.

In the Islamic world, the practice of calligraphy constitutes an expression of piety. Historically the writing of Arabic script was considered an exemplary activity for men and women of all stations due to its association with the Qur'an. In a literal sense, calligraphy leaves a trace of the physical movement of the hand. In a more abstract sense, it is also a material record of thoughts transformed into speech and then into writing. In the Islamic lands, calligraphy is understood to leave a trace of the writer's moral fiber, and the quality of writing is believed to reveal the writer's character and piety. The tools to create masterful script convey the elegance of this esteemed art form and reveal the skills of diverse artisans, from paper makers and bookbinders to gold beaters, illuminators, and metalworkers.

The varied works of calligraphy on display—from practice alphabets to elaborately finished manuscripts—serve as traces of individuals, belief systems, and cultures. The costly and exotic materials lavished on writing instruments also document the international trade of the period from 1600–1900 and create a rich material legacy that fuses aesthetics and piety.

The exhibitions were organized by the Museum of Fine Arts Houston and the Harvard University Art Museums, and were curated by Mary McWilliams, Norma Jean Calderwood Curator of Islamic and Later Indian Art at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, and David J. Roxburgh, Prince Alwaleed bin Talal Professor of Islamic Art History at Harvard University.

Support for the exhibitions in Atlanta has been provided by Emory University, the Ansary Foundation and the Honorable Mrs. Hushang Ansary, Mr. and Mrs. Vahid Kooros, His Highness Prince Aga Khan Shia Ismaili Council for the Southeastern United States, Malani Jewelers, Imperial Fez, and Emory's Department of Middle Eastern and South Asian Studies.