Cultivating America: Visions of the Landscape in Twentieth-Century Prints

Saturday, March 8, 2008 - Sunday, June 29, 2008

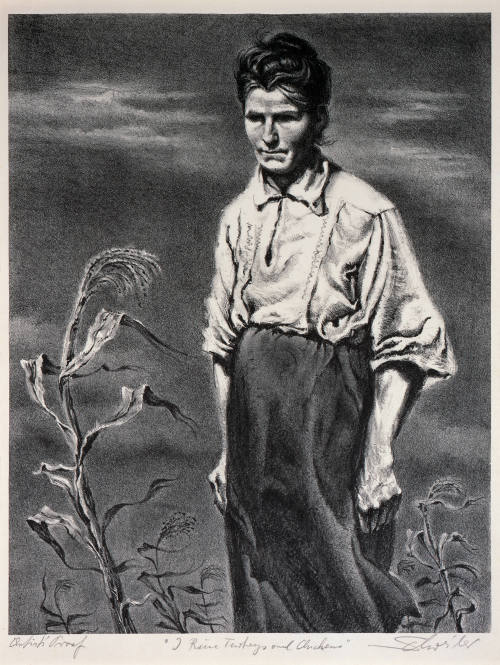

In the years between the two world wars, as America sought to establish a separate identity from Europe, critics called for a truly “American” art to be born. This art was to be democratic in spirit—accessible to all—and, thus, realist in style (as opposed to the abstraction of the European avant-garde) and distinctly American in subject matter. The artistic movement that arose in response to this call came to be known as the “American Scene.” Within the American Scene another movement, “Regionalism,” developed that focused on rural views often tinged with nostalgia for the pre-industrial past. Portrayals of the landscape helped twentieth-century Americans understand and identify with the past conquest of the frontier and solidified the idea of an American spirit rooted in the soil.

The artists in this exhibition all shared an interest in the land and the people who lived and worked upon it, yet their landscapes have many faces. The works of Albert Winslow Barker and Jac Young portray an idyllic, nurturing countryside. For others, nature is a powerful force that threatens to overwhelm the human endeavors, as it does in the brewing storm of Peppino Mangravite’s lithograph. It was also a powerful metaphor for the wartime experiences of Americans, as Marguerite Kumm and Prentiss Taylor demonstrate. Thomas Hart Benton sought to articulate the spirit of the people in the land by devoting himself to depictions of American laborers. Other artists, like John Costigan, chose a more nostalgic and personal view to express the hope that the hardships of the Depression would pass and prosperity would return. Seascapes, as in the works by Barker, Leo John Meissner, and Lawrence Wilbur, also contributed to the overall vision of the American environment.

The Great Depression, of course, made existence for both artists and their subjects increasingly difficult. Government programs were developed to combat the high unemployment rate, hiring artists to create government posters, decorate government buildings, and establish community art centers. A 1939 Works Progress Administration (WPA) exhibition catalogue spoke in agricultural terms of American artists who were “fertilizing the best elements of our heritage” and halting the erosion that threatened “to deprive large sections of America of its cultural top-soil.”

Capitalizing on the government’s promotion of American art and artists during the Depression, the American Artists Group (AAG) and Associated American Artists (AAA) were both founded as private business ventures in 1934. Trying to make a profit and provide a livelihood for artists in dire economic times, these companies marketed art to the public in a radical new way. The message of their advertising was clear: the relative affordability and multiple copies of prints made them democratic, and these particular prints were especially American in style, subject, and spirit. Before the waning of their popularity in the early 1950s, Regionalist and American Scene artists and their art would become household names, and a part of the American tradition.

The artists in this exhibition all shared an interest in the land and the people who lived and worked upon it, yet their landscapes have many faces. The works of Albert Winslow Barker and Jac Young portray an idyllic, nurturing countryside. For others, nature is a powerful force that threatens to overwhelm the human endeavors, as it does in the brewing storm of Peppino Mangravite’s lithograph. It was also a powerful metaphor for the wartime experiences of Americans, as Marguerite Kumm and Prentiss Taylor demonstrate. Thomas Hart Benton sought to articulate the spirit of the people in the land by devoting himself to depictions of American laborers. Other artists, like John Costigan, chose a more nostalgic and personal view to express the hope that the hardships of the Depression would pass and prosperity would return. Seascapes, as in the works by Barker, Leo John Meissner, and Lawrence Wilbur, also contributed to the overall vision of the American environment.

The Great Depression, of course, made existence for both artists and their subjects increasingly difficult. Government programs were developed to combat the high unemployment rate, hiring artists to create government posters, decorate government buildings, and establish community art centers. A 1939 Works Progress Administration (WPA) exhibition catalogue spoke in agricultural terms of American artists who were “fertilizing the best elements of our heritage” and halting the erosion that threatened “to deprive large sections of America of its cultural top-soil.”

Capitalizing on the government’s promotion of American art and artists during the Depression, the American Artists Group (AAG) and Associated American Artists (AAA) were both founded as private business ventures in 1934. Trying to make a profit and provide a livelihood for artists in dire economic times, these companies marketed art to the public in a radical new way. The message of their advertising was clear: the relative affordability and multiple copies of prints made them democratic, and these particular prints were especially American in style, subject, and spirit. Before the waning of their popularity in the early 1950s, Regionalist and American Scene artists and their art would become household names, and a part of the American tradition.